Fortune the Slave:

A Glimpse Into Waterbury's History

Written by Art Intel, Edited by Vincent E. Martinelli, Jr.

|

In the mid-18th century, Waterbury emerged as a small agricultural community amidst the backdrop of slavery that permeated the northern colonies. Among those whose lives were irrevocably shaped by this institution was Fortune, an enslaved man who became a poignant symbol of slavery in Connecticut.

Owned by Doctor Preserved Porter, a respected bone surgeon, Fortune lived with his wife Dinah and their children on the Porter plantation, which spanned 75 acres. The family worked tirelessly, tending to crops like rye, Indian corn, onions, potatoes, apples, and various livestock. Fortune's life was marked by the harsh realities and physical burdens of slavery. He was baptized at Saint John's Episcopal Church in Waterbury in 1797, a religious act that underscored the spiritual aspirations of enslaved individuals seeking a connection to their humanity. Tragically, just weeks after his baptism, Fortune drowned in an accident in the Naugatuck River in 1798. In a deeply disturbing turn of events, Doctor Porter chose to dissect Fortune's body for anatomical study rather than provide him a proper burial. This was not an isolated incident; during the 1700s, the practice of using human remains for medical research was relatively common, especially given the scarcity of such specimens. Fortune's remains were retained by the Porter family for decades until they were ultimately donated to the Downtown's reknowned Mattatuck Museum. His skeleton became a subject of study and was displayed as "Larry," a name that stripped him of his identity and humanity. Researchers and historians began to uncover his true story in the late 20th century, recognizing Fortune not merely as a skeleton but as a man who endured significant physical hardship over his all-too-short lifetime. In 2013, Fortune was finally given a proper burial at the famed Riverside Cemetery, marking a significant moment for the African-American community in the greater Waterbury area. This event was celebrated as a step toward acknowledging the shameful history of slavery in Waterbury and Connecticut at large, and providing Fortune with the dignity he had been denied in life. Jerry Conlogue, a researcher from Quinnipiac University, spearheaded efforts to study Fortune's remains through advanced x-ray analysis and 3-D imaging. Conlogue remarked, "My task is to find the secrets that are hidden in the bones," emphasizing the physical struggles that Fortune endured throughout his life as an enslaved man. Fortune's skeletal analysis revealed evidence of arthritis in his lower back and a fracture in his hand, indicative of a life filled with manual labor and physical strain. Conlogue noted that while the emotional experiences of Fortune's life remain elusive, the physical evidence speaks volumes about the stresses he faced. The history of slavery in Waterbury is often overlooked, with many believing that the institution was confined to the southern states. However, more than 100 people are known to have been enslaved in Waterbury over the years, a fact that challenges the narrative of northern exceptionalism. The first recorded enslaved African American in Waterbury was a boy named Mingo, who arrived in the 1730s, highlighting that the roots of slavery in the region run deep. Throughout the 1700s, laws in Connecticut reflected a hierarchical society that marginalized Native Americans and African Americans. Enslaved individuals were often viewed as property, with little regard for their humanity. The economy of the time was agrarian, and many professionals, including doctors and ministers, were slave owners. This reliance on slave labor was indicative of a broader societal acceptance of slavery, despite emerging abolitionist sentiments that would eventually lead to gradual emancipation. The story of Fortune and the broader history of slavery in Waterbury has gained renewed attention through community-driven history projects, such as the "Ties That Bind" exhibit at the Mattatuck Museum. This project, developed in collaboration with the African American History Project Committee, aimed to illuminate the experiences of enslaved individuals in the area and confront the whitewashing of history. In recent years, Fortune's story has been brought to life through the work of historians and researchers who are committed to uncovering the truth about slavery in Waterbury, and in Connecticut, and of the North East. The permanent exhibit at the Mattatuck Museum serves as a vital resource for educating visitors about the realities of slavery, emphasizing the importance of recognizing Fortune as a man rather than merely a piece of property. A local history enthusiast remarked, “He was a man who was a slave. It’s a mindset that is very different,” highlighting the need to humanize the narratives of enslaved individuals. As the community continues to grapple with its past, the efforts to remember and honor Fortune serve as a reminder of the resilience of those who endured the horrors of slavery. In conclusion, Fortune's life and legacy are emblematic of the broader struggle against the injustices of slavery in Connecticut. From his tragic death to the eventual recognition of his humanity, his story invites reflection on the enduring impact of slavery and the importance of acknowledging and preserving the history of all who lived through this dark chapter. Through ongoing research and community engagement, there is hope that future generations will gain a deeper understanding of this critical part of Waterbury’s history. Notes

Although no conclusive evidence of relationshp has been found, Doctor Preserved Porter, and/or his family, may have owned property that is currently known as the South End District's East End Neighborhood. Specifically, the general area north of Park Road (in the East End Neighborhood, not Park Road in the West Side Manor Neighborhood, the Bunker Hill Neighborhood, nor the West End Neighborhood), north of Plank Road, south of Meriden Road, and around Southmayd Road was parceled between Timothy Porter, Elias Porter, James Porter, Joseph Porter, and others. These parcels may have been part of Doctor Preserved Porters plantation. Similarly, no evidence has been found to indicat that the areas surrounding Porter Street, which is no known as Porter Street and West Porter Street, are of any relation to the Porter Plantation. Sources, Resources, and Additional ReadingBooks

Articles and Journals

Online Resources

Documentaries and Films

Research and Archives

|

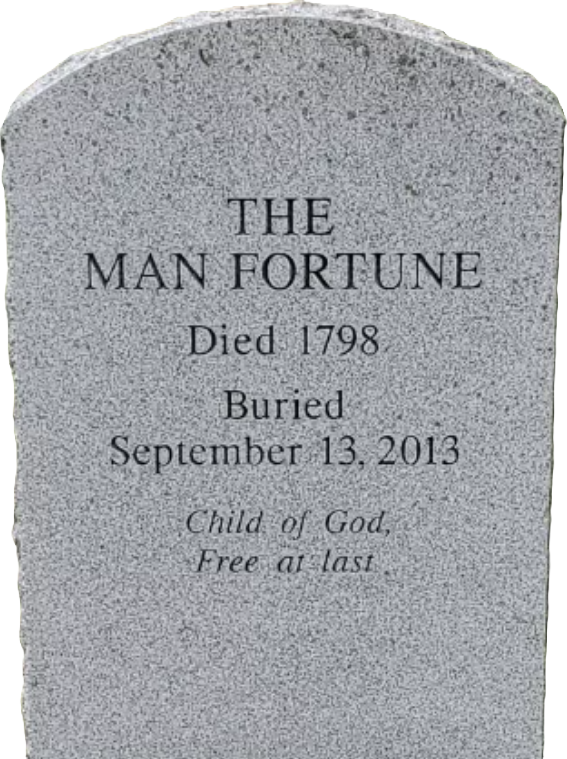

Fortune's TombstoneFortune was born circa 1743 and died in 1798. He was buried 215 years later.

Source: Grunge

|